According to legend, giant pandas were once pure white. Perhaps this is why the story’s heroine – a young Chinese shepherd girl – occasionally encountered friendly pandas among her white sheep. Disaster struck one day: a marauding leopard attacked one of the girl’s panda friends. The girl rushed into the fray to try to save the panda, who escaped with his life. The girl was not so lucky. When the panda told the others of the girl’s death, they were devastated. As a symbol of their mourning, the pandas coated their front legs with ashes. As they dried their tears, the ashes stained their eyes black. As they held each other close, the ashes colored their shoulders. As their keening wails of grief grew too loud to bear, the pandas raised their paws to their ears, turning them black, too. Ever since, giant pandas have borne the black stains.

Tuesday, May 3, 2011

Tuesday, April 19, 2011

Invisible City

The fighting still goes on between the faithful and the rebels. The inhabitants of the city of Zaira have grown accustom to war in the town. The Brotherhood of the Black Keys have defended the castle for thousands of years. Through countless battles they have survived and stayed faithful, but times are changing and people are revolting. A man sleeps inside a small shack in the cramped and crowded town below the fortress of Zaira. The room cooled by the zinc roofs that use to be but now covered by the tarps over the rickety frame work and ruined stone houses. The young guy a member of The Raven Rebels have been fighting for freedom from the ruthless grip of the rulers in the citadel on the hill. He grabs a can of spray paint and tosses it into his bag with an assortment of other things needed for a day in the lawless city of Zaira. He pulls a hood over his head to help hide his face and straps his bag on his back. As he walks he navigates through the haphazard buildings stacked on one another carelessly. He finds a secluded spot and pulls out a spray can. Kids run by the end of the street where he is, they laugh and scream as they kick a ball between them. He starts to move as he sprays writing the phrase FIGHT with a guy holding up his fist next to it. He steps back and looks to the right to see a man in a robe staring at him. Fear hits the boy as he runs the opposite way from the robed man. His robe flies open as he lifts a gun from the holster and aims it at the young rebel. The kid sees he stuck in a corner so he runs up the wall and jumps over to the roof of another home as gun fire explodes and bullets dig into the stone wall where he was. The kid runs to a street as a car explodes and he ducks into another ally. He quickly climbs on the roof and pulls a small automatic gun from his bag. He screams as he joins in the fight, he squeezes the trigger and the gun ignites and fire burst from the tips rapidly. Men in robes blast guns at young men and boys as they shout and fire back. In the distance you see the Castle of Zaira surrounded by the massive wall daring any to challenge.

Sunday, April 17, 2011

The Legend of The Panda

According to legend, giant pandas were once pure white. Perhaps this is why the story’s heroine – a young Chinese shepherd girl – occasionally encountered friendly pandas among her white sheep. Disaster struck one day: a marauding leopard attacked one of the girl’s panda friends. The girl rushed into the fray to try to save the panda, who escaped with his life. The girl was not so lucky. When the panda told the others of the girl’s death, they were devastated. As a symbol of their mourning, the pandas coated their front legs with ashes. As they dried their tears, the ashes stained their eyes black. As they held each other close, the ashes colored their shoulders. As their keening wails of grief grew too loud to bear, the pandas raised their paws to their ears, turning them black, too. Ever since, giant pandas have borne the black stains.

Tuesday, March 22, 2011

Invisible city

The fighting still goes on between the faithful and the rebels. The inhabitants of the city of Zaira have grown accustom to war in the town. The Brotherhood of the Black Keys have defended the castle for thousands of years. Through countless battles they have survived and stayed faithful, but times are changing and people are revolting. A man sleeps inside a small shack in the cramped and crowded town below the fortress of Zaira. The room cooled by the zinc roofs that use to be but now covered by the tarps over the rickety frame work and ruined stone houses. The young guy a member of The Raven Rebels have been fighting for freedom from the ruthless grip of the rulers in the citadel on the hill. He grabs a can of spray paint and tosses it into his bag with an assortment of other things needed for a day in the lawless city of Zaira. He pulls a hood over his head to help hide his face and straps his bag on his back. As he walks he navigates through the haphazard buildings stacked on one another carelessly. He finds a secluded spot and pulls out a spray can. Kids run by the end of the street where he is, they laugh and scream as they kick a ball between them. He starts to move as he sprays writing the phrase FIGHT with a guy holding up his fist next to it. He steps back and looks to the right to see a man in a robe staring at him. Fear hits the boy as he runs the opposite way from the robed man. His robe flies open as he lifts a gun from the holster and aims it at the young rebel. The kid sees he stuck in a corner so he runs up the wall and jumps over to the roof of another home as gun fire explodes and bullets dig into the stone wall where he was. The kid runs to a street as a car explodes and he ducks into another ally. He quickly climbs on the roof and pulls a small automatic gun from his bag. He screams as he joins in the fight, he squeezes the trigger and the gun ignites and fire burst from the tips rapidly. Men in robes blast guns at young men and boys as they shout and fire back. In the distance you see the Castle of Zaira surrounded by the massive wall daring any to challenge.

Wednesday, February 16, 2011

Monday, February 14, 2011

Research Part 2

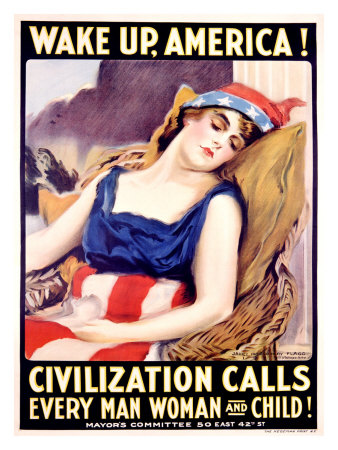

James Montgomery Flagg

James Montgomery Flagg (June 18, 1877 – May 27, 1960) was an American artist and illustrator. He worked in media ranging from fine art painting to cartooning, but is best remembered for his propaganda posters.

Flagg was born in Pelham Manor, New York. He was enthusiastic about drawing from a young age, and had illustrations accepted by national magazines by the age of 12 years. By 14 he was a contributing artist for Life magazine, and the following year was on the staff of another magazine, Judge. From 1894 through 1898, he attended the Art Students League of New York. He studied fine art in London and Paris from 1898–1900, after which he returned to the United States, where he produced countless illustrations for books, magazine covers, political and humorous cartoons, advertising, and spot drawings. Among his creations was a comic strip that appeared regularly in Judge from 1903 until 1907, about a tramp character titled Nervy Nat.

In 1915 he accepted commissions from Calkins and Holden to create advertisements for Edison Photo and Adler Rochester Overcoats but only on the condition that his name would not be associated with the campaign.

He created his most famous work in 1917, a poster to encourage recruitment in the United States Army during World War I. It showed Uncle Sam pointing at the viewer (inspired by a British recruitment poster showing Lord Kitchener in a similar pose) with the caption "I Want YOU for U.S. Army". Over four million copies of the poster were printed during World War I, and it was revived for World War II. Flagg used his own face for that of Uncle Sam (adding age and the white goatee), he said later, simply to avoid the trouble of arranging for a model.

At his peak, Flagg was reported to have been the highest paid magazine illustrator in America. In 1946 Flagg published his autobiography, Roses and Buckshot.

James Montgomery Flagg died in New York City and was interred at Woodlawn Cemetery.

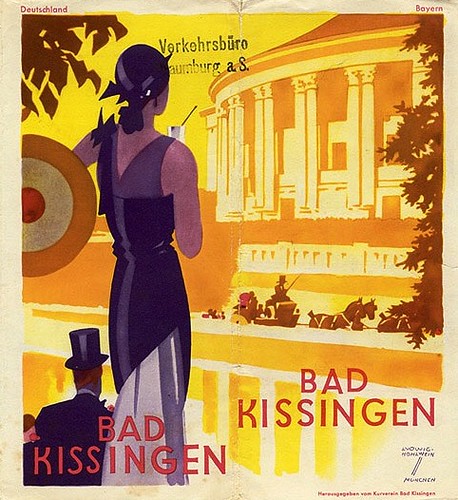

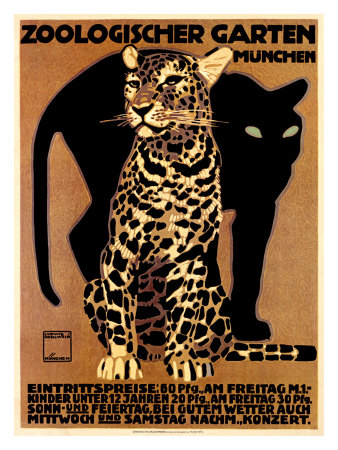

Hohlwein's high tonal contrasts and a network of interlocking shapes made his work instantly recognizable. Hohlwein was employed by the German government during the First World War to produce propaganda posters. Ludwig Hohlwein died in 1939.

Her distinctive and bold artistic style developed quickly (influenced by what Lhote sometimes referred to as "soft cubism" and by Denis' "synthetic cubism") and epitomized the cool yet sensual side of the Art Deco movement. For her, Picasso "embodied the novelty of destruction". She thought that many of the Impressionists drew badly and employed "dirty" colors. De Lempicka's technique would be novel, clean, precise, and elegant.

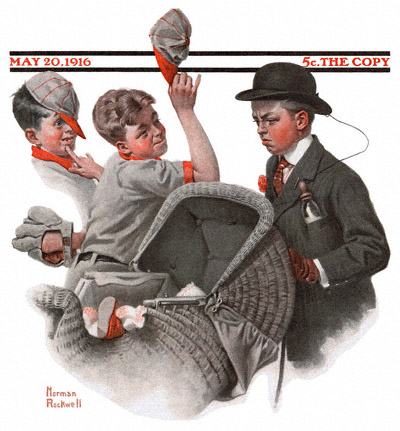

Joseph Christian Leyendecker

was one of the pre-eminent American illustrators of the early 20th century. He is best known for his poster, book, and advertising illustrations, the trade character known as The Arrow Collar Man, and his numerous covers for the Saturday Evening Post. Between 1896 and 1950, Leyendecker painted more than 400 magazine covers. During ‘The Golden Age of American Illustration’, for the Saturday Evening Post alone, J. C. Leyendecker produced 322 covers, as well as many advertisement illustrations for its interior pages. No other artist, until the arrival of Norman Rockwell two decades later, was so solidly identified with one publication. Leyendecker "virtually invented the whole idea of modern magazine design." As the premier cover illustrator for the enormously popular Saturday Evening Post for much of the first half of the 20th century, Leyendecker's work both reflected and helped mold many of the visual aspects of the era's culture in America. The mainstream image of Santa Claus as a jolly fat man in a red fur-trimmed coat was popularized by Leyendecker, as was the image of the New Year Baby. The tradition of giving flowers as a gift on Mother's Day was started by Leyendecker's May 30, 1914 Saturday Evening Post cover depicting a young bellhop carrying hyacinths. It was created as a commemoration of President Woodrow Wilson's declaration of Mother's Day as an official holiday that year.

Leyendecker was a chief influence upon, and friend of, Norman Rockwell, who was a pallbearer at Leyendecker's funeral. In particular, the early work of Norman Rockwell for the Saturday Evening Post bears a strong superficial resemblance to that of Leyendecker. While today it is generally accepted that Norman Rockwell established the best-known visual images of Americana, in many cases they are derivative of Leyendecker's work, or reinterpretations of visual themes established by Rockwell's idol.

The visual style of Leyendecker's art inspired the graphics in The Dagger of Amon Ra, a game for the PC. The museum in the game is named for Leyendecker, and the box art for the game is based on Leyendecker's cover for the March 18, 1905 issue of the Saturday Evening Post.[citation needed]

Leyendecker's drawing style was cited as a major influence on the character designs of Team Fortress 2, a first person shooter game for the PC, Xbox 360, and PlayStation 3.

Maxfield Parrish

was an American painter and illustrator active in the first half of the twentieth century. He is known for his distinctive saturated hues and idealized neo-classical imagery.

Parrish's art features dazzlingly luminous colors; the color Parrish blue was named in acknowledgement. He achieved the results by means of a technique called glazing where bright layers of oil color separated by varnish are applied alternately over a base rendering (Parrish usually used a blue and white monochromatic underpainting).

He would build up the depth in his paintings by photographing, enlarging, projecting and tracing half- or full-size objects or figures. Parrish then cut out and placed the images on his canvas, covering them with thick, but clear, layers of glaze. The result is realism of elegiac vivacity. His work achieves a unique three-dimensional appearance, which does not translate well to coffee table books.

The outer proportions and internal divisions of Parrish's compositions were carefully calculated in accordance with geometric principles such as root rectangles and the golden ratio. In this Parrish was influenced by Jay Hambidge's theory of Dynamic Symmetry. Parrish devised many innovative techniques which no other major artist has successfully copied. A technique which Parrish used frequently involved creating a large piece of cloth with a geometric pattern in stark black-and-white (such as alternate black and white squares, or a regular pattern of black circles on a white background). A human model (often Parrish himself) would then pose for a photograph with this cloth draped naturally on his or her body in a manner which intentionally distorted the pattern. Parrish would develop a transparency of the photo, then project this onto the canvas of his current work in progress. Using black graphite on the white canvas, Parrish would painstakingly trace and fill in all the black portions of the projected photo. The result was astonishing: in the finished painting, a human figure would be seen wearing a distinctive geometrically-patterned cloth which draped realistically and accurately.

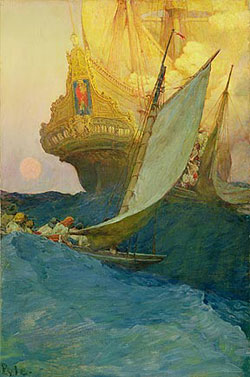

Howard Pyle

was an American illustrator and writer, primarily of books for young audiences. A native of Wilmington, Delaware, he spent the last year of his life in Florence, Italy.

In 1894 he began teaching illustration at the Drexel Institute of Art, Science and Industry (now Drexel University), and after 1900 he founded his own school of art and illustration called the Howard Pyle School of Illustration Art. The term the Brandywine School was later applied to the illustration artists and Wyeth family artists of the Brandywine region by Pitz (later called the Brandywine School). Some of his more famous students were Olive Rush, N. C. Wyeth, Frank Schoonover, Elenore Abbott, Ellen Bernard Thompson Pyle, Allen Tupper True, Anna Whelan Betts, Ethel Franklin Betts, Harvey Dunn and Jessie Willcox Smith.

His 1883 classic The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood remains in print to this day, and his other books, frequently with medieval European settings, include a four-volume set on King Arthur that cemented his reputation.

He wrote an original novel, Otto of the Silver Hand, in 1888. He also illustrated historical and adventure stories for periodicals such as Harper's Weekly and St. Nicholas Magazine. His novel Men of Iron was made into a movie in 1954, The Black Shield of Falworth.

Pyle travelled to Florence, Italy to study mural painting in 1910, and died there in 1911 of sudden kidney infection (Bright's Disease).

Arthur Rackham

was an English book illustrator. In 1892 he quit his job and started working for The Westminster Budget as a reporter and illustrator. His first book illustrations were published in 1893 in To the Other Side by Thomas Rhodes, but his first serious commission was in 1894 for The Dolly Dialogues, the collected sketches of Anthony Hope, who later went on to write The Prisoner of Zenda. Book illustrating then became Rackham's career for the rest of his life.

In 1903 he married Edyth Starkie, with whom he had one daughter, Barbara, in 1908. Rackham won a gold medal at the Milan International Exhibition in 1906 and another one at the Barcelona International Exposition in 1912. His works were included in numerous exhibitions, including one at the Louvre in Paris in 1914. Arthur Rackham died 1939 of cancer in his home in Limpsfield, Surrey.

Rackham invented his own unique technique which resembled photographic reproduction; he would first sketch an outline of his drawing, then lightly block in shapes and details. Afterwards he would add lines in pen and India ink, removing the pencil traces after it had dried. With color pictures, he would then apply multiple washes of color until transparent tints were created. He would also go on to expand the use of silhouette cuts in illustration work.

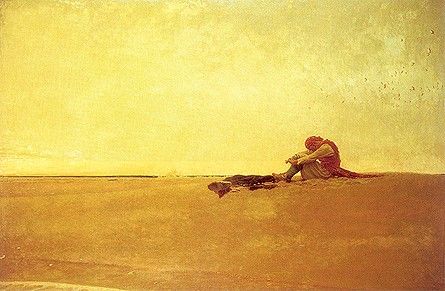

Frederic Remington

was an American painter, illustrator, sculptor, and writer who specialized in depictions of the Old American West, specifically concentrating on the last quarter of the 19th century American West and images of cowboys, American Indians, and the U.S. Cavalry.

Remington was the most successful Western illustrator in the “Golden Age” of illustration at the end of the 19th Century and the beginning of the 20th Century, so much so that the other Western artists such as Charles Russell and Charles Schreyvogel were known during Remington’s life as members of the “School of Remington”. His style was naturalistic, sometimes impressionistic, and usually veered away from the ethnographic realism of earlier Western artists such as George Catlin. His focus was firmly on the people and animals of the West, with landscape usually of secondary importance, unlike the members and descendants of the Hudson River School, such as Frederic Edwin Church, Albert Bierstadt, and Thomas Moran, who glorified the vastness of the West and the dominance of nature over man. He took artistic liberties in his depictions of human action, and for the sake of his readers’ and publishers’ interest. Though always confident in his subject matter, Remington was less sure about his colors, and critics often harped on his palette, but his lack of confidence drove him to experiment and produce a great variety of effects, some very true to nature and some imagined.

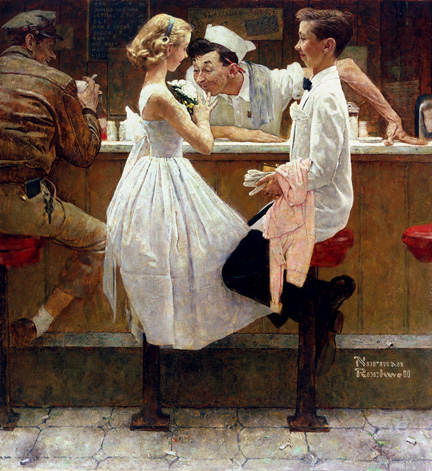

Norman Rockwell

was a 20th-century American painter and illustrator. His works enjoy a broad popular appeal in the United States, where Rockwell is most famous for the cover illustrations of everyday life scenarios he created for The Saturday Evening Post magazine for more than four decades. Among the best-known of Rockwell's works are the Willie Gillis series, Rosie the Riveter (although his Rosie was reproduced less than others of the day), Saying Grace (1951), and the Four Freedoms series. He is also noted for his work for the Boy Scouts of America (BSA); producing covers for their publication Boys' Life, calendars, and other illustrations.

Egon Schiele

was an Austrian painter. A protégé of Gustav Klimt, Schiele was a major figurative painter of the early 20th century.

Schiele's work is noted for its intensity, and the many self-portraits the artist produced. The twisted body shapes and the expressive line that characterize Schiele's paintings and drawings mark the artist as an early exponent of Expressionism, although still strongly associated with the art nouveau movement (Jugendstil).

The Leopold Museum, Vienna houses perhaps Schiele's most important and complete collection of work, featuring over 200 exhibits. Other notable collections of Schiele's art include the Egon Schiele-Museum, Tulln and Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna.

Jessie Willcox Smith

was a United States illustrator famous for her work in magazines such as Ladies Home Journal and for her illustrations for children's books.

Born in the Mount Airy neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1884 Smith attended the School of Design for Women (which is now Moore College of Art & Design) and later studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts under Thomas Eakins in Philadelphia, graduating in 1888. A year later, she started working in the production department of the Ladies' Home Journal, for five years. She left to take classes under Howard Pyle, first at Drexel and then at the Brandywine School.

She was a prolific contributor to books and magazines during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, illustrating stories and articles for clients such as Century, Collier's Weekly, Leslie's Weekly, Harper's, McClure's, Scribners, and the Ladies' Home Journal.

Smith may be most well known for her covers on Good Housekeeping, which she painted from December 1917 through March 1933. She also painted posters and portraits. Her twelve illustrations for Charles Kingsley's The Water-Babies (1916) are also well known. On Smith's death, she bequeathed the original works to the Library of Congress' "Cabinet of American Illustration" collection. (A thirteenth illustration remains in a private collection.)

The Hall of Fame of the Society of Illustrators has inducted only 10 women since its inception in 1958. Smith was the second after Lorraine Fox. Of those ten, three of them occupied the same house, Cogslea, as the Red Rose Girls. Elizabeth Shippen Green and Violet Oakley were fellow Howard Pyle students that shared that space, which was arguably the finest collection of illustrative talent ever in American life. Smith's papers are deposited in the collection of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

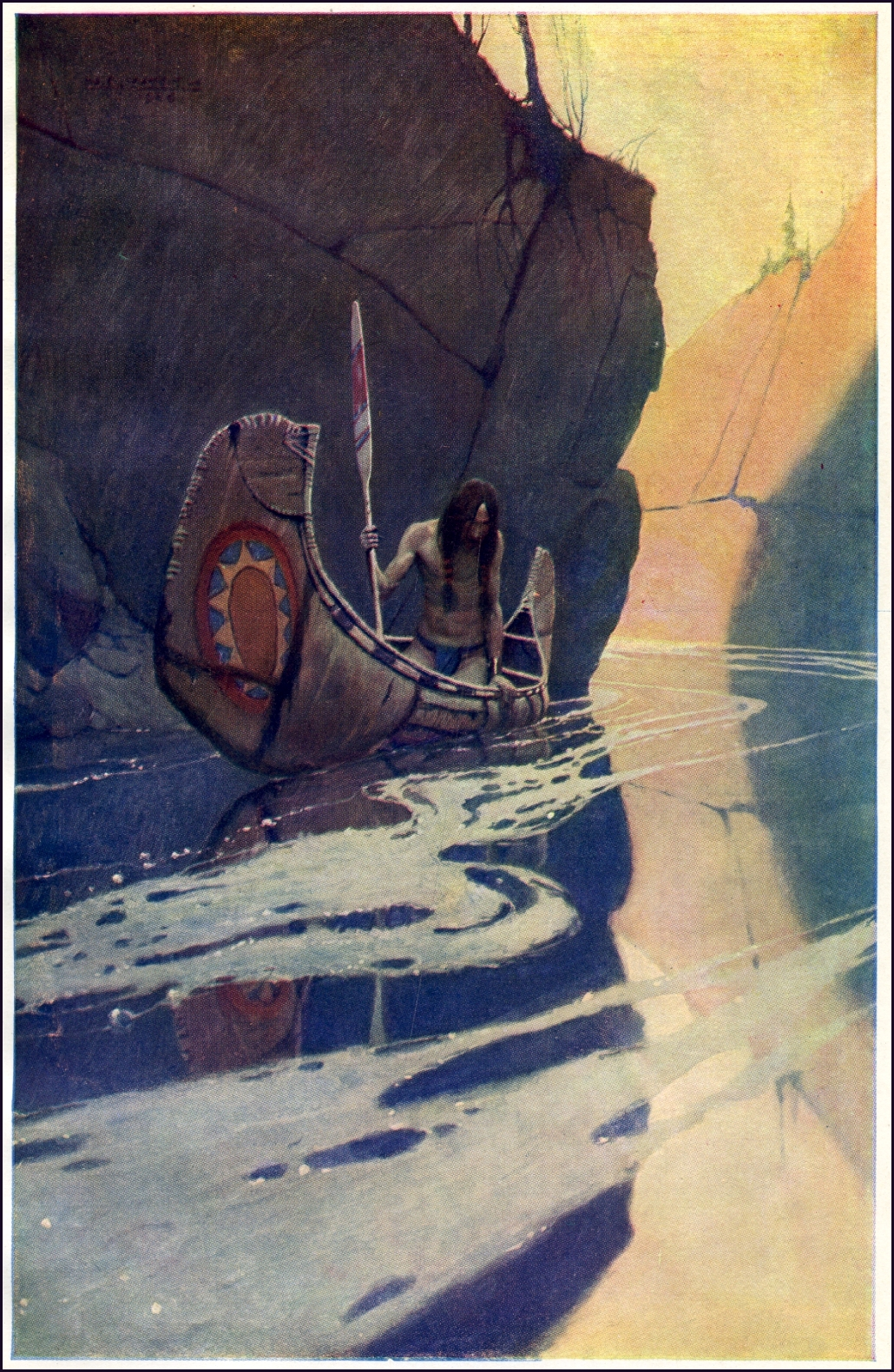

N.C. Wyeth

Newell Convers Wyeth (October 22, 1882 – October 19, 1945), known as N.C. Wyeth, was an American artist and illustrator. He was the star pupil of artist Howard Pyle and became one of America's greatest illustrators.

During his lifetime, Wyeth created over 3,000 paintings and illustrated 112 books,[2] 25 of them for Scribner's, which is the work for which he is best-known.

Wyeth was a realist painter just as the camera and photography began to compete with his craft.[3] Sometimes seen as melodramatic, his illustrations were designed to be understood quickly.[4] Wyeth, who was both a painter and an illustrator, understood the difference, and said in 1908, "Painting and illustration cannot be mixed—one cannot merge from one into the other."

James Montgomery Flagg (June 18, 1877 – May 27, 1960) was an American artist and illustrator. He worked in media ranging from fine art painting to cartooning, but is best remembered for his propaganda posters.

Flagg was born in Pelham Manor, New York. He was enthusiastic about drawing from a young age, and had illustrations accepted by national magazines by the age of 12 years. By 14 he was a contributing artist for Life magazine, and the following year was on the staff of another magazine, Judge. From 1894 through 1898, he attended the Art Students League of New York. He studied fine art in London and Paris from 1898–1900, after which he returned to the United States, where he produced countless illustrations for books, magazine covers, political and humorous cartoons, advertising, and spot drawings. Among his creations was a comic strip that appeared regularly in Judge from 1903 until 1907, about a tramp character titled Nervy Nat.

In 1915 he accepted commissions from Calkins and Holden to create advertisements for Edison Photo and Adler Rochester Overcoats but only on the condition that his name would not be associated with the campaign.

He created his most famous work in 1917, a poster to encourage recruitment in the United States Army during World War I. It showed Uncle Sam pointing at the viewer (inspired by a British recruitment poster showing Lord Kitchener in a similar pose) with the caption "I Want YOU for U.S. Army". Over four million copies of the poster were printed during World War I, and it was revived for World War II. Flagg used his own face for that of Uncle Sam (adding age and the white goatee), he said later, simply to avoid the trouble of arranging for a model.

At his peak, Flagg was reported to have been the highest paid magazine illustrator in America. In 1946 Flagg published his autobiography, Roses and Buckshot.

James Montgomery Flagg died in New York City and was interred at Woodlawn Cemetery.

Ludwig Hohlwein

Ludwig Hohlwein was born in Germany in 1874. He trained as an architect and practised until 1906 when he started a new career in poster design. He quickly established himself as one of the most important people working in this field in Germany. Hohlwein's high tonal contrasts and a network of interlocking shapes made his work instantly recognizable. Hohlwein was employed by the German government during the First World War to produce propaganda posters. Ludwig Hohlwein died in 1939.

Tamara de Lempicka

born Maria Górska in Warsaw, in partitioned Poland, was a Polish Art Deco painter and "the first woman artist to be a glamour star." In Paris, the Lempickis lived for a while from the sale of family jewels. Tadeusz proved unwilling or unable to find suitable work, which added to the domestic strain, while Maria gave birth to Kizette de Lempicka.Her distinctive and bold artistic style developed quickly (influenced by what Lhote sometimes referred to as "soft cubism" and by Denis' "synthetic cubism") and epitomized the cool yet sensual side of the Art Deco movement. For her, Picasso "embodied the novelty of destruction". She thought that many of the Impressionists drew badly and employed "dirty" colors. De Lempicka's technique would be novel, clean, precise, and elegant.

Joseph Christian Leyendecker

was one of the pre-eminent American illustrators of the early 20th century. He is best known for his poster, book, and advertising illustrations, the trade character known as The Arrow Collar Man, and his numerous covers for the Saturday Evening Post. Between 1896 and 1950, Leyendecker painted more than 400 magazine covers. During ‘The Golden Age of American Illustration’, for the Saturday Evening Post alone, J. C. Leyendecker produced 322 covers, as well as many advertisement illustrations for its interior pages. No other artist, until the arrival of Norman Rockwell two decades later, was so solidly identified with one publication. Leyendecker "virtually invented the whole idea of modern magazine design." As the premier cover illustrator for the enormously popular Saturday Evening Post for much of the first half of the 20th century, Leyendecker's work both reflected and helped mold many of the visual aspects of the era's culture in America. The mainstream image of Santa Claus as a jolly fat man in a red fur-trimmed coat was popularized by Leyendecker, as was the image of the New Year Baby. The tradition of giving flowers as a gift on Mother's Day was started by Leyendecker's May 30, 1914 Saturday Evening Post cover depicting a young bellhop carrying hyacinths. It was created as a commemoration of President Woodrow Wilson's declaration of Mother's Day as an official holiday that year.

Leyendecker was a chief influence upon, and friend of, Norman Rockwell, who was a pallbearer at Leyendecker's funeral. In particular, the early work of Norman Rockwell for the Saturday Evening Post bears a strong superficial resemblance to that of Leyendecker. While today it is generally accepted that Norman Rockwell established the best-known visual images of Americana, in many cases they are derivative of Leyendecker's work, or reinterpretations of visual themes established by Rockwell's idol.

The visual style of Leyendecker's art inspired the graphics in The Dagger of Amon Ra, a game for the PC. The museum in the game is named for Leyendecker, and the box art for the game is based on Leyendecker's cover for the March 18, 1905 issue of the Saturday Evening Post.[citation needed]

Leyendecker's drawing style was cited as a major influence on the character designs of Team Fortress 2, a first person shooter game for the PC, Xbox 360, and PlayStation 3.

Maxfield Parrish

was an American painter and illustrator active in the first half of the twentieth century. He is known for his distinctive saturated hues and idealized neo-classical imagery.

Parrish's art features dazzlingly luminous colors; the color Parrish blue was named in acknowledgement. He achieved the results by means of a technique called glazing where bright layers of oil color separated by varnish are applied alternately over a base rendering (Parrish usually used a blue and white monochromatic underpainting).

He would build up the depth in his paintings by photographing, enlarging, projecting and tracing half- or full-size objects or figures. Parrish then cut out and placed the images on his canvas, covering them with thick, but clear, layers of glaze. The result is realism of elegiac vivacity. His work achieves a unique three-dimensional appearance, which does not translate well to coffee table books.

The outer proportions and internal divisions of Parrish's compositions were carefully calculated in accordance with geometric principles such as root rectangles and the golden ratio. In this Parrish was influenced by Jay Hambidge's theory of Dynamic Symmetry. Parrish devised many innovative techniques which no other major artist has successfully copied. A technique which Parrish used frequently involved creating a large piece of cloth with a geometric pattern in stark black-and-white (such as alternate black and white squares, or a regular pattern of black circles on a white background). A human model (often Parrish himself) would then pose for a photograph with this cloth draped naturally on his or her body in a manner which intentionally distorted the pattern. Parrish would develop a transparency of the photo, then project this onto the canvas of his current work in progress. Using black graphite on the white canvas, Parrish would painstakingly trace and fill in all the black portions of the projected photo. The result was astonishing: in the finished painting, a human figure would be seen wearing a distinctive geometrically-patterned cloth which draped realistically and accurately.

Howard Pyle

was an American illustrator and writer, primarily of books for young audiences. A native of Wilmington, Delaware, he spent the last year of his life in Florence, Italy.

In 1894 he began teaching illustration at the Drexel Institute of Art, Science and Industry (now Drexel University), and after 1900 he founded his own school of art and illustration called the Howard Pyle School of Illustration Art. The term the Brandywine School was later applied to the illustration artists and Wyeth family artists of the Brandywine region by Pitz (later called the Brandywine School). Some of his more famous students were Olive Rush, N. C. Wyeth, Frank Schoonover, Elenore Abbott, Ellen Bernard Thompson Pyle, Allen Tupper True, Anna Whelan Betts, Ethel Franklin Betts, Harvey Dunn and Jessie Willcox Smith.

His 1883 classic The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood remains in print to this day, and his other books, frequently with medieval European settings, include a four-volume set on King Arthur that cemented his reputation.

He wrote an original novel, Otto of the Silver Hand, in 1888. He also illustrated historical and adventure stories for periodicals such as Harper's Weekly and St. Nicholas Magazine. His novel Men of Iron was made into a movie in 1954, The Black Shield of Falworth.

Pyle travelled to Florence, Italy to study mural painting in 1910, and died there in 1911 of sudden kidney infection (Bright's Disease).

Arthur Rackham

was an English book illustrator. In 1892 he quit his job and started working for The Westminster Budget as a reporter and illustrator. His first book illustrations were published in 1893 in To the Other Side by Thomas Rhodes, but his first serious commission was in 1894 for The Dolly Dialogues, the collected sketches of Anthony Hope, who later went on to write The Prisoner of Zenda. Book illustrating then became Rackham's career for the rest of his life.

In 1903 he married Edyth Starkie, with whom he had one daughter, Barbara, in 1908. Rackham won a gold medal at the Milan International Exhibition in 1906 and another one at the Barcelona International Exposition in 1912. His works were included in numerous exhibitions, including one at the Louvre in Paris in 1914. Arthur Rackham died 1939 of cancer in his home in Limpsfield, Surrey.

Rackham invented his own unique technique which resembled photographic reproduction; he would first sketch an outline of his drawing, then lightly block in shapes and details. Afterwards he would add lines in pen and India ink, removing the pencil traces after it had dried. With color pictures, he would then apply multiple washes of color until transparent tints were created. He would also go on to expand the use of silhouette cuts in illustration work.

Frederic Remington

was an American painter, illustrator, sculptor, and writer who specialized in depictions of the Old American West, specifically concentrating on the last quarter of the 19th century American West and images of cowboys, American Indians, and the U.S. Cavalry.

Remington was the most successful Western illustrator in the “Golden Age” of illustration at the end of the 19th Century and the beginning of the 20th Century, so much so that the other Western artists such as Charles Russell and Charles Schreyvogel were known during Remington’s life as members of the “School of Remington”. His style was naturalistic, sometimes impressionistic, and usually veered away from the ethnographic realism of earlier Western artists such as George Catlin. His focus was firmly on the people and animals of the West, with landscape usually of secondary importance, unlike the members and descendants of the Hudson River School, such as Frederic Edwin Church, Albert Bierstadt, and Thomas Moran, who glorified the vastness of the West and the dominance of nature over man. He took artistic liberties in his depictions of human action, and for the sake of his readers’ and publishers’ interest. Though always confident in his subject matter, Remington was less sure about his colors, and critics often harped on his palette, but his lack of confidence drove him to experiment and produce a great variety of effects, some very true to nature and some imagined.

Norman Rockwell

was a 20th-century American painter and illustrator. His works enjoy a broad popular appeal in the United States, where Rockwell is most famous for the cover illustrations of everyday life scenarios he created for The Saturday Evening Post magazine for more than four decades. Among the best-known of Rockwell's works are the Willie Gillis series, Rosie the Riveter (although his Rosie was reproduced less than others of the day), Saying Grace (1951), and the Four Freedoms series. He is also noted for his work for the Boy Scouts of America (BSA); producing covers for their publication Boys' Life, calendars, and other illustrations.

Egon Schiele

was an Austrian painter. A protégé of Gustav Klimt, Schiele was a major figurative painter of the early 20th century.

Schiele's work is noted for its intensity, and the many self-portraits the artist produced. The twisted body shapes and the expressive line that characterize Schiele's paintings and drawings mark the artist as an early exponent of Expressionism, although still strongly associated with the art nouveau movement (Jugendstil).

The Leopold Museum, Vienna houses perhaps Schiele's most important and complete collection of work, featuring over 200 exhibits. Other notable collections of Schiele's art include the Egon Schiele-Museum, Tulln and Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna.

Jessie Willcox Smith

was a United States illustrator famous for her work in magazines such as Ladies Home Journal and for her illustrations for children's books.

Born in the Mount Airy neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1884 Smith attended the School of Design for Women (which is now Moore College of Art & Design) and later studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts under Thomas Eakins in Philadelphia, graduating in 1888. A year later, she started working in the production department of the Ladies' Home Journal, for five years. She left to take classes under Howard Pyle, first at Drexel and then at the Brandywine School.

She was a prolific contributor to books and magazines during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, illustrating stories and articles for clients such as Century, Collier's Weekly, Leslie's Weekly, Harper's, McClure's, Scribners, and the Ladies' Home Journal.

Smith may be most well known for her covers on Good Housekeeping, which she painted from December 1917 through March 1933. She also painted posters and portraits. Her twelve illustrations for Charles Kingsley's The Water-Babies (1916) are also well known. On Smith's death, she bequeathed the original works to the Library of Congress' "Cabinet of American Illustration" collection. (A thirteenth illustration remains in a private collection.)

The Hall of Fame of the Society of Illustrators has inducted only 10 women since its inception in 1958. Smith was the second after Lorraine Fox. Of those ten, three of them occupied the same house, Cogslea, as the Red Rose Girls. Elizabeth Shippen Green and Violet Oakley were fellow Howard Pyle students that shared that space, which was arguably the finest collection of illustrative talent ever in American life. Smith's papers are deposited in the collection of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

N.C. Wyeth

Newell Convers Wyeth (October 22, 1882 – October 19, 1945), known as N.C. Wyeth, was an American artist and illustrator. He was the star pupil of artist Howard Pyle and became one of America's greatest illustrators.

During his lifetime, Wyeth created over 3,000 paintings and illustrated 112 books,[2] 25 of them for Scribner's, which is the work for which he is best-known.

Wyeth was a realist painter just as the camera and photography began to compete with his craft.[3] Sometimes seen as melodramatic, his illustrations were designed to be understood quickly.[4] Wyeth, who was both a painter and an illustrator, understood the difference, and said in 1908, "Painting and illustration cannot be mixed—one cannot merge from one into the other."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)